Table of Contents

Chapter 3 – FUNDAMENTAL ANALYSIS AND ABSOLUTE RETURNS

Chapter 4 – RESEARCH PROCESS: COMPANY ANALYSIS

Chapter 5 – RESEARCH PROCESS: VALUATION ANALYSIS

Chapter 6 – MARGIN OF SAFETY IN TECHNOLOGY INVESTMENTS

Chapter 7 – INTERNATIONAL STOCKS: SAMSUNG CASE STUDY

Chapter 8 – TECHNOLOGY INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE

Chapter 9 – INVESTORS BEHAVING BADLY

Chapter 10 – ACTIVE VS. PASSIVE INVESTING

Chapter 11 – DEALING WITH INVESTMENT MISTAKES

Chapter 12 – SOURCES OF INFORMATION

Chapter 13 – ASPIRATIONAL IDEAS FOR INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT

APPENDIX 1 – Harnessing the Power of Microsoft OneNote

APPENDIX 2 – An Overview of Sentieo

APPENDIX 3 – Counterpoint Technology Research

APPENDIX 4 – inSpectrum: Semiconductor Industry Intelligence

Preface

I decided to write this book for two reasons – 1) to inform and educate the individual investor and the public at large, and share my perspectives about the otherwise “black box” world of institutional equity research, and its clients, institutional investment managers; and suggest an approach for the individual investor to take advantage of deficiencies in the institutional system, and 2) to share a process that I practiced with considerable success, for analyzing investments in technology companies, during my 9+ year career as an equity research analyst, following a 9-year career in the technology industry, as an engineer. I believe the core elements of my process would be highly applicable to investments in other (non-tech) sectors as well. I have written this book with a broad audience in mind, from individual investors to career changers, to buyside analysts who might have been tasked with researching technology companies in particular. My hope is that the information and discussion in this book will also be insightful and perhaps entertaining to others that may not necessarily have a specific agenda but are nevertheless curious about the financial services industry.

I have noticed frequent misunderstanding and misperception of the role of a sellside equity research analyst (aka “stock analyst”, “Wall Street analyst”) working for an investment bank, perhaps because sufficient efforts haven’t been collectively made to inform the public about the functions and responsibilities of the role, or frankly because a sellside equity research analyst isn’t really supposed to have individual investors as his or her clients. It’s a profession that isn’t as well advertised to MBA graduates from top programs, as compared to transactional investment banking roles for example. It’s certainly not a profession that I aspired to pursue growing up, and I am quite sure neither do others. For various such reasons, I don’t think the average investor is well equipped to interpret research reports written by sellside analysts. Instead it would seem a lot more convenient to just blame the analysts for one’s independent investing missteps.

When it comes to the buyside – and this I know first-hand as well, thanks to countless discussions with a range of highly intelligent investors around the world, relentless pursuit of short-term relative performance continues to reign supreme, perhaps based on an implicit assumption that such short-term relative performance is also of critical importance to individual investors. For example - if you lost 50% of your assets, would it matter if the stock market was down 60% and you outperformed the market? An individual investor is unlikely to find such outperformance impressive when faced with substantial loss of principal, yet a fund manager would tout such outperformance as basis for growing assets under management. Focus on the short term not only drives higher trading costs and management fees, but also a structural handicap; and resulting (often predictable) behavior by institutional money-managers creates opportunities for individual investors (or their independent wealth managers) to protect and grow their investments.

A better understanding of the cast and characters of the investment world should in theory enable individual investors to make more informed decisions about managing their investments. Specifically, my hope is that individual investors that read this book, would be encouraged to question their choice of stocks, mutual funds, or investment managers, in case they haven’t executed a similar “house cleaning” recently. Having an investment manager whose interests and goals are aligned with your own, is obviously important to your financial success. It fascinates me that individuals work very hard through their lives to earn substantial amounts of cash, only to hand it over to money managers (e.g. mutual funds) that on average have different goals than those individuals whom the cash belongs to. The financial services industry I think thrives on the ignorance of its clients, especially individual investors.

I have been a student of the philosophy of value investing, which of course was established, executed, and popularized by superinvestors Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffet, and Seth Klarman among others. In this book I describe a research process that applies the tenets of value investing to the task of identifying profitable investments in the technology sector. The punchline here is that if you have a strong academic and/or industry background in technology, understand how disruptive new high-tech products are created, and other politics of the tech industry, then you stand to have an advantage over the average professional investor in evaluating investments in tech stocks, assuming you can also gain mastery of the research process, and remember to follow process discipline at all times. That may of course be a lot to ask for, especially if identifying investments or managing money is not your primary occupation – it isn’t for most people. Still, insight into such a process that a skilled investment manager could execute on your behalf, should provide more visibility (and therefore comfort) into a mechanism that would be used to protect and grow your investments.

Here’s what I hope to gain from writing this book – 1) satisfaction that I have made an effort to help my family, friends, and well-wishers understand what I did for 9+ years of my career in equity research, and why I was too busy to spend more time with people that wanted and deserved my company, 2) a basis for mutually rewarding personal and professional relationships as a trusted advisor, and 3) a codified reference for process elements that I diligently developed and practiced but didn’t previously have a chance to document. Deep in my heart I would like to help individual investors by sharing my knowledge and experience, even if for a small fee, because I strongly believe in two things – 1) individual investors whose funds are being managed deserve to know the process of investing and the basis for selecting specific investments being made on their behalf, and 2) sharing investment theses for individual stocks (and the process behind developing such theses) with individual investors would only reinforce process discipline by allowing the validity of such investment theses to be re-examined frequently. These are not standard processes followed by the average active investment manager today, and my hope is that this book serves as a change agent in that regard. Investment managers should be held to a higher standard, not just per force through compliance, but also through active education of individual investors.

I expect about a third of the readers of this book to dismiss it as common knowledge. I expect another third of the readers to find the information presented either incomplete, too abstract or difficult to follow. I expect the remainder of the readers to find the book interesting, if only for its chosen presentation format filled with illustrations, and I expect that a portion of these readers will seek out assistance from an investment manager to apply their learnings to their investment portfolios.

The process of identifying and managing investments should involve a lot of discussion, to make sure that the key assumptions or objectives are well communicated and mutually understood. In that spirit, I have included below advice for contacting me, should you have follow up questions or need help. Keep in mind that this book comes with FREE access to additional online resources such as case studies and stock pitch examples – see website information below.

Advice for contacting me:

Readers: [email protected]

Case Studies, Stock Pitch Examples: www.bajikartechinvestor.com

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/sbajikar

Twitter: @SundeepBajikar, #bajikartechinvestor

Facebook: www.facebook.com/ertechinvestor

Chapter 11 - Dealing With Investment Mistakes

Nobody likes to make mistakes, but reality is that mistakes do happen from time to time, and are guaranteed to occur in the world of investing. So the question is not whether you will make mistakes, but rather how you will deal with mistakes. A lot of the discussion in this chapter is probably not unique to investing, but certainly more important to the world of investing, where the basis of most transactions is rooted in client trust. It takes a long time to build trust, but just a moment to lose it. Since I spent a lot of time discussing my investment process and how or why it was successful earlier in the book, I thought it necessary to add this chapter about investment mistakes, so that I could come clean about at least a couple of mistakes I know I have made.

Does your favorite mutual fund or hedge fund make investment mistakes? Are those mistakes and their resolution communicated to you? If you are paying a management fee for someone to manage your investments, shouldn’t they provide sufficient transparency for you to know how your investment manager is making investment decisions? Does reading a quarterly or yearly newsletter satisfy all your curiosities about how your assets are being managed? How does your investment manager determine she has made a mistake? What’s your investment manager’s process for rectifying mistakes?

I recently asked a well-known portfolio manager at a well-reputed mutual fund that prides itself in its fundamental analysis-driven investing process, what his process was to determine whether he had made a mistake with a particular stock. His answer – “the market tells us that we made a mistake”. Do you think that answer is consistent with his stated strategy of fundamental analysis, based on everything we discussed in this book so far? Unless he is holding a stock for a short-term trade, a fundamentals-driven manager should not be looking to the market to tell him whether he picked the right stock. For a fundamentals-driven manager, determination of a stock selection error would occur only upon learning that he made a mistake in analyzing underlying business fundamentals, which he should be tracking carefully. At least he was honest, or perhaps he didn’t have a chance to think about his answer. Either way, his response is certainly not unique, and a number of honest and well-known portfolio managers will probably answer the same way. Perhaps this serves to highlight the tension that such managers live with every day – to advertise to their clients that the fund is fundamentals-driven, but accept the reality that fund managers look to the market for answers far too often than they should.

In this chapter I am going to discuss a couple of the mistakes I have made in my investment analyses over the years, and what I have learnt from them.

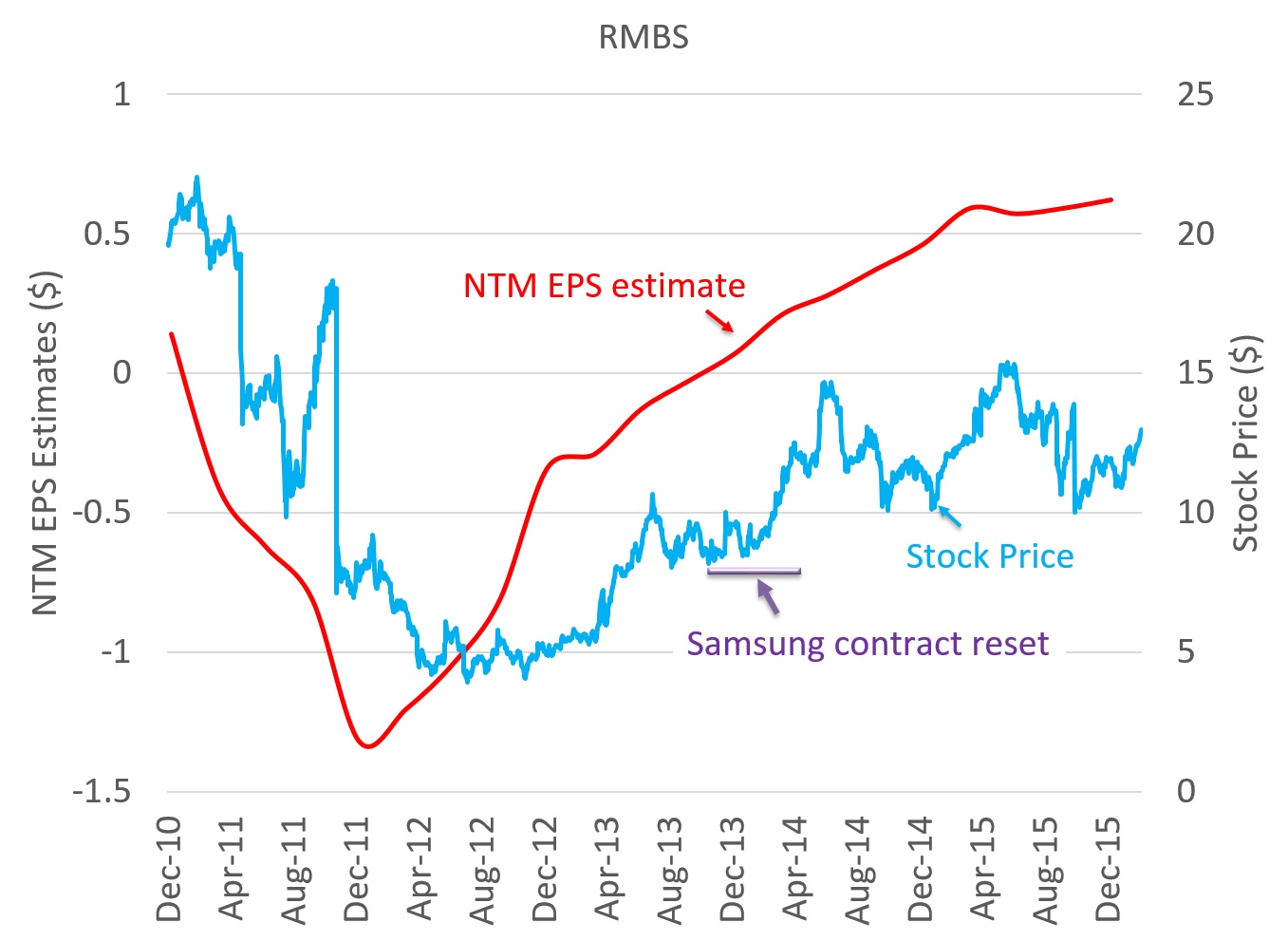

RMBS case study – Samsung contract reset

I initiated coverage of RMBS in December 2013 with a Buy rating because I was convinced that a positive inflection in Samsung’s DRAM revenues would translate into commensurately positive inflection in Rambus’ DRAM-related royalties from Samsung. After having analyzed the DRAM industry in detail, and estimating a high correlation between Samsung’s DRAM revenues and Rambus’ DRAM-related royalties from Samsung, I was confident that significant earnings upside was likely for RMBS. In early-January 2014, just a few weeks after my initiation of coverage, Rambus announced that Samsung had reset its contract with Rambus to a lower rate of royalties. With my primary investment thesis on the stock having proven wrong by an unexpected contract reset, I downgraded the stock to a Hold rating on the news.

The problem here was the binary nature of the fundamentals driving the Buy recommendation. Even though there was nothing wrong with my analysis, there wasn’t enough of a margin of safety in the Buy recommendation, given that it was singularly driven by DRAM upside, assuming Samsung would continue to pay royalties at the existing rate. The Rambus case study underscored the need to have a multi-factor investment thesis, such that if one of the factors didn’t play out as expected, you could still hold on to the stock for other reasons. That unfortunately was not the framework I had used for Rambus.

The next case study illustrates that even after having a multi-factor investment thesis, it is possible to be wrong on a stock, again due to no specific fault of your own except perhaps that you didn’t anticipate the level of expectations already baked into the stock before deciding to buy it.

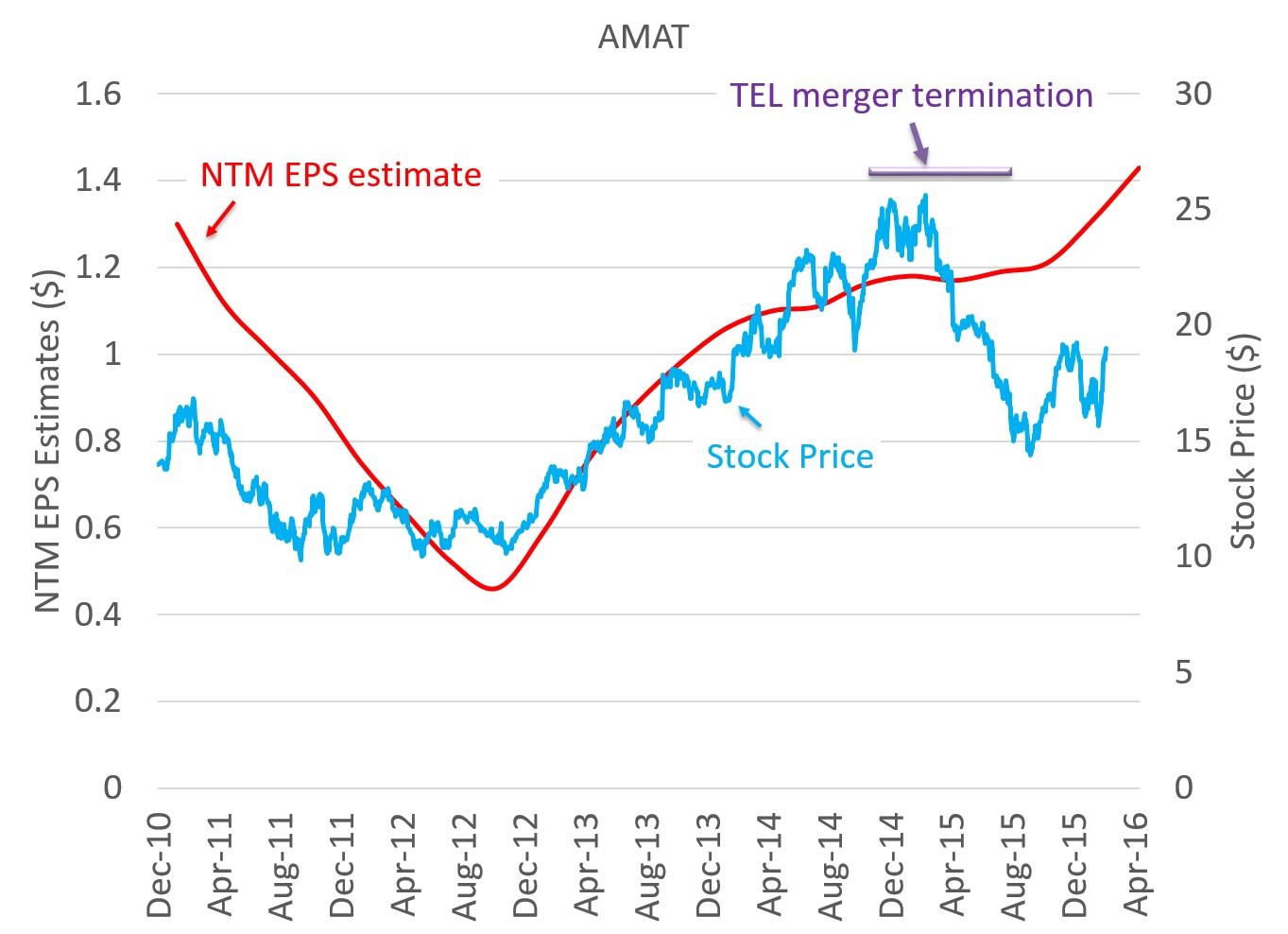

AMAT case study – TEL merger termination

I recommended Applied Materials (NASDAQ: AMAT) with a Buy rating starting in early-2014, based on a multi-factor secular thesis, which included a positive inflection due to AMAT’s planned merger with Tokyo Electron (TEL). Following several delays, AMAT finally announced in early 2015 that it had terminated its merger agreement with TEL due to regulatory hurdles in closing the merger. Following announcement of termination of its TEL merger, AMAT stock took a big hit, from the mid-$20s to the mid-$teens. The mistake I made here was not accounting for a sufficient margin of safety with my Buy recommendation.

If you look at the red line (NTM EPS estimate) in the chart above, you can interpret that standalone fundamentals for AMAT had performed solidly as of this writing, and this suggests that non-merger-related positive secular factors included in my Buy thesis played out more or less as expected. Not properly assessing how much merger-related euphoria was already baked into the stock price, was the mistake here. Since early-2014, AMAT had consistently traded at a NTM P/E multiple of ~18x, i.e. roughly in line with its peer group. In other words, AMAT was not trading at a significant valuation discount, and had not significantly underperformed in the period leading to my Buy recommendation. If you compare these factors to the framework I presented in Chapter 6, you will find that the margin of safety considerations were not satisfactorily met. Treating the TEL-merger as a high-probability scenario was the culprit.

As it turns out, as of this writing, secular fundamentals for AMAT I thought were still positive, virtually for the same reasons that they were positive in early 2014 (ex-TEL). With the stock having underperformed due to the TEL-merger debacle, the stock carried a higher margin of safety trading in the mid-$teens, though the stock’s valuation multiple remained healthy.

Why Value Investing in Technology is Difficult for Generalists

The chart below is a modified version of a chart you saw in Chapter 3 where we discussed what drives stock prices. This chart dissects “Company Fundamentals” into “Business Model” and “Industry Dynamics”. While a generalist value investor would be capable of understanding the business model of a technology company, she may not fully understand the influence that various industry dynamics might have on the company’s business model. This affects the process of assessing intrinsic value, and introduces risk in the investment process, making the process difficult to execute successfully.

As I have said throughout this book, if you are investing in technology stocks, but don’t think you have a strong understanding of underlying technology industry dynamics, then I’m afraid you might be misleading yourself or your investors. Furthermore, your chosen investment strategy is then most definitely not “fundamentals-driven”, but rather driven by some other short-term oriented trading strategy that may or may not have a popular name – like “technical trading” or “swing trading” or “momentum trading”.

Next in Chapter 12, I provide a framework to think about different types of information and data that are available to a technology investor, and discuss my best practices for using such information.